Community & Business

11 May, 2025

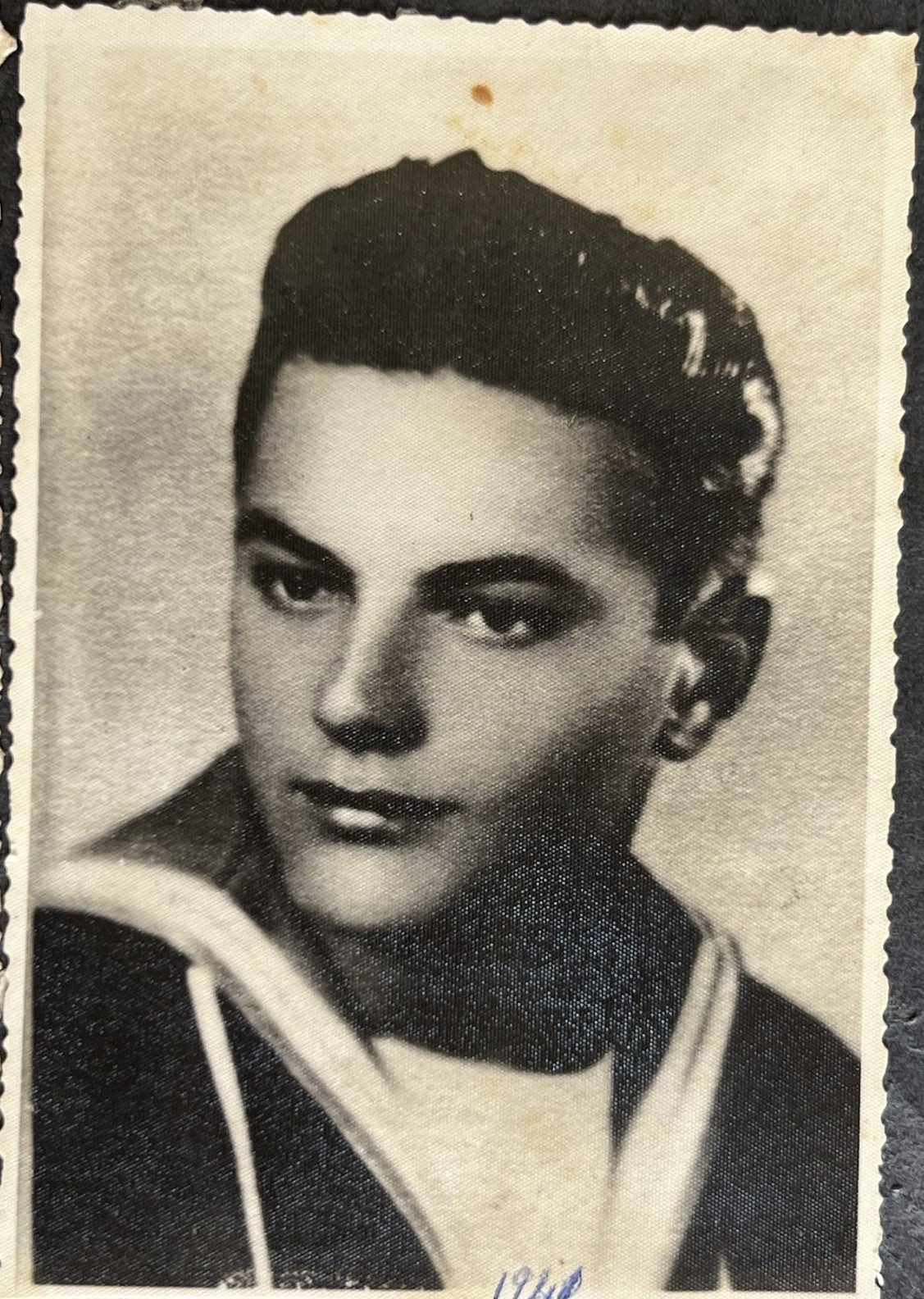

Andy’s journey through time

HE has witnessed so many changes in a long life - world war, television, passenger planes, the rise and fall of the tobacco growing industry, computers, the internet and mobile phones. To younger generations it would be like time travel.

But when asked what the most impactful moments of his 100 years have been, Andrea Inveradi recalls two things: his papa waving and smiling just before he was accidentally killed, and the moment he saw his wife and first-born arrive on Australian soil.

The bittersweet memories were life-changing, yet Andy, as he is known, smiles when he describes with clarity, both incidents.

He is sitting on a chair outside the room that he shares with his wife Adelaide at Carinya Home in Atherton. He is fit, lean, and sharp. His exercise bike, used for two hours each day, sits on the porch overlooking a fenced-off, but lush, grounds.

Just a couple of days earlier he and his family and friends celebrated his centenary, with cakes, balloons, and letters from His Majesty the King, the Prime Minister, the Governor General of Australia, and of Queensland, the Premier and many local, federal and state politicians.

He moved to Carinya a few weeks after his wife, about 18 months ago. Adelaide, who suffers from dementia, was assessed as too vulnerable to remain at their farm near Dimbulah.

“I stayed at home for a little while, I didn’t want to be here,” he sighs and smiles, looking over at the bed where Adelaide is resting.

“But it was just me, the rock wallabies and the dog. I needed to be with her. I had no one to talk to.”

It isn’t often you meet a person who has migrated twice to Australia, but then again, it isn’t often you meet a person who’s long life is so intertwined with key moments in modern Australian history.

Born on 29 April, 1925, in Rovato, Brescia, in Lombardy, Northern Italy, he spent his first two years with his baby brother, Rocco, before his father took up an opportunity to go to Australia in 1927. He was to work at a cousin’s cane farm near Ingham and build a new life for his family, as the Depression took hold around the world.

Three years later, the family arrived by boat to reunite with Andy’s father. His dad had bought an old tin hut behind the Ingham hospital, which had belonged to a Chinese gardener who had passed on. Accommodation at the cane farm was for workers only.

It was in poor condition following a great flood of the time, but Andy’s dad rebuilt and added another room. It was basic living, with no power, one bed and no water. The brothers slept on the floor, their number growing to four - Andy, Rocco, Angelo, Frankie and baby sister Angelina sleeping with Mum and Dad.

They relied on the creek next to which they lived for water.

“We grew a little bit of corn and vegies, and then we would sell it to people. A penny here, half penny there, we got by with the little money we could save,” Andy says.

“Aborigines were living on the other side of the creek, we had no problem,” Andy shrugged. “They’d come over and ask for a bit of sugar, come up and get a bit of tea and stuff.”

Andy went to school with the nuns, but wasn’t learning well.

“The nuns used to come out every Sunday and visit and they’d say ‘where’s Andy?’, (I used to play the wag). They’d say ‘sometimes he’s a good boy, sometimes he’s a cheeky boy’,” Andy chuckles.

His father moved him to the state school to see if he would improve.

That didn’t last long. Andy came home crying one afternoon after his teacher had called him a “Dago”. Furious, his beloved father took him back to the nun’s school.

Then Andy’s life changed forever.

“My dad said to my mum one day, ‘tell Andrea not to stop and play marbles at school, tell him to come home straight away, go to the paddock and catch the horse, put him on to the horse cart and we go towards Halifax. Tell him I have bought him a spring bed!”

At 5pm, Andy had the cart ready and the two of them took off to Halifax, climbing up and out from their Creekside home.

“At the top of the hill Dad stopped and waved back to Mum and the rest of the family. He’d never done that before,” Andy says, a half smile, his bright eyes earnest.

“Four times a week we’d go around and sell vegies, he never stopped and waved. He’d never done it before.”

As they continued they neared the railway line and a sugar cane truck was headed to Victoria Mill for the crush.

“Dad was still standing up, and I was kneeling in front of him. The truck tooted its horn, you had to do that before you crossed the line. It frightened the horse, which did a sharp curve and Dad fell. I ended up a couple of hundred yards away on the ground, when the horse stopped because a wheel got caught in a fence post.

“I wasn’t hurt, and I ran back and a few good guys who were there got in touch with the ambos. In those days we didn’t have a phone. I didn’t wait for the ambulance, I ran home.”

“When I got there, mum said ‘the sergeant came to see me. I didn’t understand what he said, but he had tears in his eyes.’”

Andy told his mum what happened and the following morning a nurse called in to say they had better come up to the hospital.

“I ran. He was still alive, but unconscious. I was with him. Before Mum and the family got there he passed away,” he says.

“Mum could never, never get over it. Didn’t matter how many times the nuns came down to visit, she never got over it.

“We had no money, the Australian people didn’t like us very much because Mussolini went against England. I was being called Dago at school.

“Mum wanted to go back to Italy.

The family took up an offer by former PM, and then fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, for Italian migrants to return home for free. It was six months before World War II began.

Back in Italy, Andy’s family was helped by his mother’s uncle, who was a priest. Life was still hard, work was scarce, and Andy, close to 16, decided to join the navy without his mother’s knowledge.

“I always liked the navy,” he says. “I was in the submarines.”

He recalls the turning point for him in the war.

“We were given six days at home, and we knew very well, you don’t get six days off during a war. When we come back it’s got to be a big mission.”

They were right. They were to intercept British vessels going to Malta near the Red Sea.

“When we got there, they were waiting for us. They knew we were coming. We had no choice but to turn back.”

Andy says they all knew the war was ending, and they were on the wrong side. Many simply walked away when they returned to Italy.

The war ended, Andy got reconstruction work in Milan, and after a time noticed a young lady on the train. It was Adelaide. After a few shy conversations, they started dating. But life was still tough, and “there was a lot of anger in Italy”.

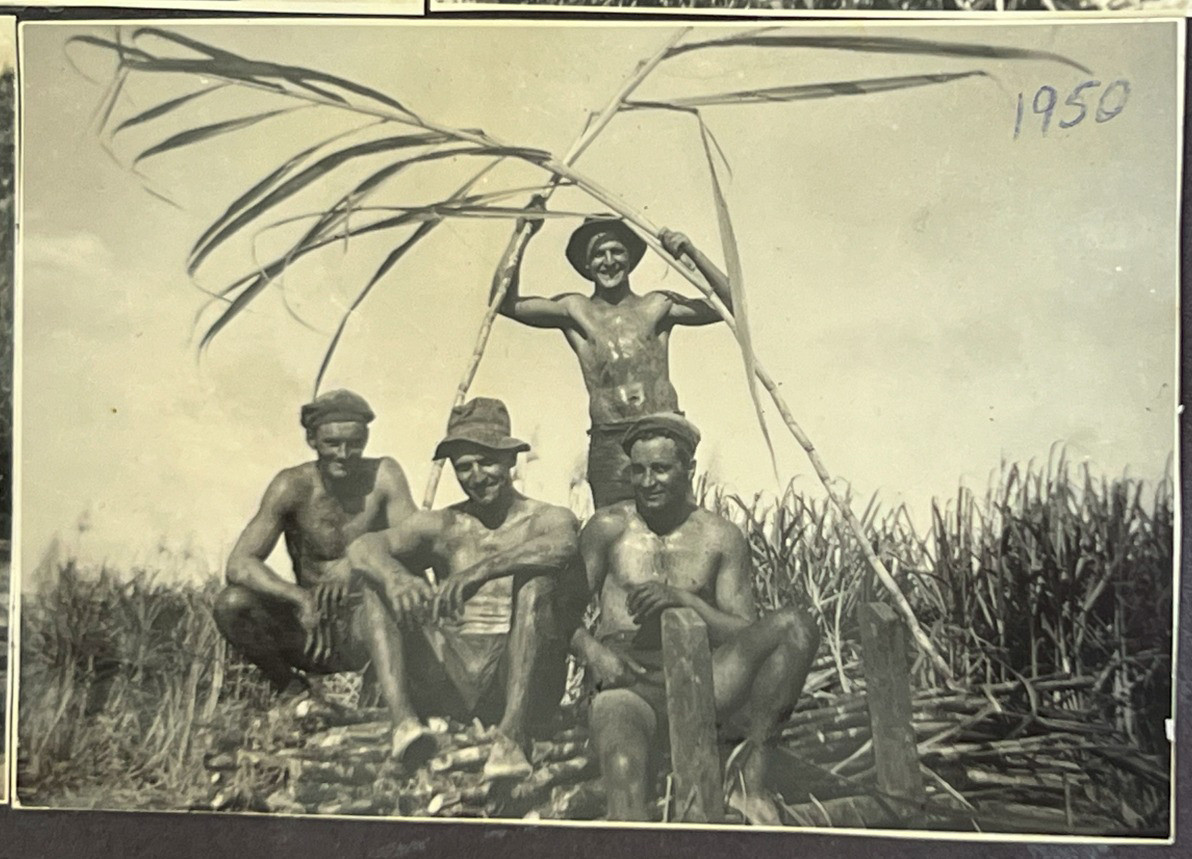

A cousin in Australia had a cane farm near Tully, close to country he had grown up in. By 1949, Andy for the second time in his life, moved to Australia.

“I went to Euramo and cut cane, just like Dad,” he smiles. “I really enjoyed it.”

He had planned for Adelaide to come out when he was settled, but it would take at least two years as his girlfriend. As fate would have it, it was not long after he arrived that his mother wrote to tell him he was to be a father.

“I did the wrong thing in the first place, but I fixed it up in the second place,” Andy says a little embarrassed.

The couple were married by proxy, 72 years ago; Andy with a priest beside him in Tully, while Adelaide was with a priest in Italy.

Then the happiest moment of his life happened.

“When I saw Adelaide with my son Emelio. It was nothing special,” he shrugs. “But to me, we were married, and I saw my baby for the first time.”

By the time his family was growing, Emelio joined by brother Victor and sister Laura, and his mother and siblings all settling in and around the region, Andy took on new challenges.

He trained and bought the bakery in Euramo from a friend who had provided the family with free bread.

A few years later he bought the Gordonvale bakery. It was a gamble. The bakery had been shut for years, as the previous owner had not been able to “turn a good loaf”.

When Andy did a bit of investigating he found the oven firebox was in the wrong place and heat was distributing badly. He got a mate from the mill to fix it and his first loaf was just right.

After several years Andy had itchy feet and thought about buying a cane farm in Aloomba. But the bank manager had told him he was better off heading to the Tablelands where tobacco growing was the big earner.

The family moved to a farm near Dimbulah, which produced a low standard of tobacco, as the soil was poor. But undeterred Andy bought a second farm near sandy creek which proved much more successful.

“I knew nothing about tobacco, but, steady, steady it became a good life.”

The family thrived and in the town Andy became a well-known producer, and community member.

“Then they got sick of us growing tobacco, and we had to stop. And they gave us $4 a kilo! Whatever quality you had. Which you’d be flat out buying a house in town it wasn’t much,” he says with a hint of bitterness.

Andy stayed farming, introducing navy beans, which he shut down after several years as there were “too many navy beans”.

He then began tea tree oil production, he adds laughing with self-deprecation. After expensive fitting out, machinery distilling, and so forth, tea trees also took a dive.

“I said Andrea, it’s time to give it up. I didn’t know what to damn plant. Tobacco was the best.”

He sold both farms and bought another farm, this time to relax and retire. He bought a push bike and spent days riding. He’d go to church every Sunday (which he still does), go bowling, and just enjoyed living easy.

They still have the farm, and his daughter who works in mining, will visit and take him there when she can.

He feels a little frustrated at the inactivity of living in a care wing of Carinya, surrounded by people who need assistance. But it’s what it is. It’s a nice place he says, for people who need looking after.

Staff help when they can by accompanying him on outside walks, or by taking him to the gym - which he loves - but he misses bike riding.

He has visitors, and of course the odd incredible birthday parties. His sister Angelina even made it to his 100th. His brothers have all passed now.

And he has his beloved Adelaide.

“Oh yes, we argue every day, we get divorced every day,” he grins.

Something he wouldn’t miss for the world.